Aus Heft 89: Primitivgeldsammler 34/1, 40-47 (2013) ; Bei korrekter Zitierweise ist die Übernahme von kleineren Text-Ausschnitten ohne Rückfrage erlaubt.

by Bernhard Rabus

In their book „Tridacna gigas – Objets de Prestige en Mélanesie“ (2011) the authors Eric Lancrenon and Didier Zanette argue on pages 135 and 136 that kesa are not made from Tridacna clam shell but from the tube of a Kuphus. The accuracy of this statement and its basic principles are reviewed in the following.

1. Preliminary remarks

The American anthropologist Harold Scheffler (Choiseul Island Social Structure, 1965), who is cited as their main source by the authors, stayed on Choiseul 50 years before them and much longer than they did. His informants presumably do not live anymore and yet even at his time nobody could remember the time when kesa were made. Therefore I tend to rely more on Scheffler’s book concerning kesa than on the more recent observations by the authors and statements of today’s inhabitants of Choiseul. The second authority the authors refer to is A. Capell (1943). Capell was never on Choiseul himself but evaluated the literature available to him. I have analyzed his texts very thoroughly and have come to the conclusion that he confused kesa from Choiseul with shell money from Bougainville (see paragraph 7).

I will discuss what I, unlike the authors, think kesa were made from, but the method how they were made will remain a mystery.

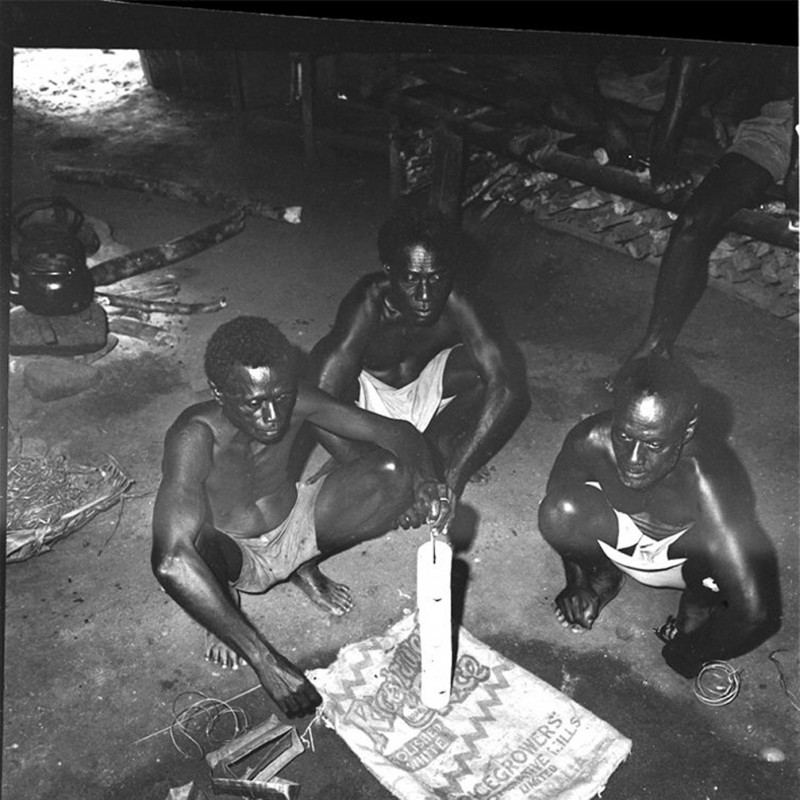

- Aufstellen und Ausmessen der neun mata Zylinder einer kesa Einheit auf Choiseul.

(Foto Harold W. Scheffler 1958-1961. Quelle: UC San Diego: Manderville Special Collections Library)

2. Basic assumptions

2.1 Terminology of „kesa“

At first the object of our investigation should be defined clearly. On the island of Choiseul one monetary unit of kesa consists of three packets of salaka, each of which contains three single cylinders named mata or lupe. The authors agree with that (page 136). So one kesa consists of nine cylinders. During exchange all nine are put on top of each other (standing up) and the pile must stand freely without aid. The title picture of this issue shows the result of this procedure. Scheffler recorded it in a series of pictures. His description: „This series shows the process of standing up kesa in order to display and measure it, as was conventional procedure in all kesa transactions. Wrappings are of ivory nut palm leaf and the measuring stick, which also prevents the rickety stack from falling, is the mid-rib of the leaf. The kesa must stand freely and be neatly arranged, but the rough edges of the thin shell makes this difficult. The man in the center is the owner of this kesa, which is worth five small kesa, and he shows obvious delight in this display. Kesa larger than this one were given personal names, and their histories were carefully remembered and related by the owners“. So the kesa shown on the title picture belongs to the most valuable class within „working kesa“ (kesa zazu = working or kesa soka = for exchange, according to Scheffler). Single rings or cylinders, whether large or small, may be valuable but they are no kesa.

2.2 Distinction of „large kesa“ and „working kesa“

The authors distinguish between „large kesa“ and „working kesa“ (page 135), referring to Harold Scheffler (1965). This is correct. According to Scheffler „large kesa“ are prestige objects used only on important occasions, whereas „working kesa“ serve for normal payments. What is the difference between the two?

The authors come to the false conclusion that according to Scheffler the thickness of the cylinders is the main criterion for this distinction. Scheffler, however, describes kesa in general as „thin-walled“. In fact he distinguishes the two forms primarily by the total height of the nine cylinders put on one another. After stating the height of the biggest and most valuable „working kesa“ (estimated by me to measure 55 – 60cm based on his indications) – see paragraph 2.3 – he writes: „The largest kesa anyone claimed to have seen was over a fathom in length, and each individual mata was said to measure from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the small finger over an outstretched hand“ (Scheffler, page 201). This corresponds roughly to 20cm for each cylinder. So a „large kesa“ consists of nine cylinders (can also be eight or ten, Scheffler says) which are higher than the largest „working kesa“, up to the fabulous 1.80 meters mentioned by Scheffler; the thickness of the walls can be more than that of „working kesa“. Whether the single ring or cylinder held by a man in the picture on page 138 and named „large kesa“ was part of a kesa is unfortunately not explicitly mentioned.

2.3 Size and value grades of „working kesa“

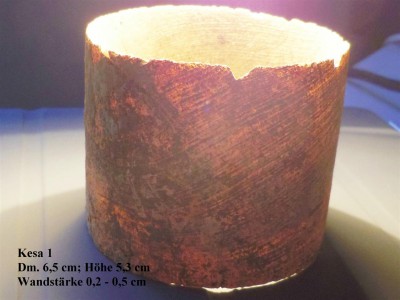

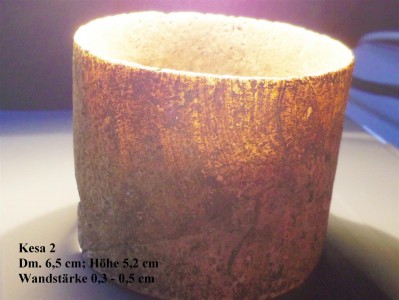

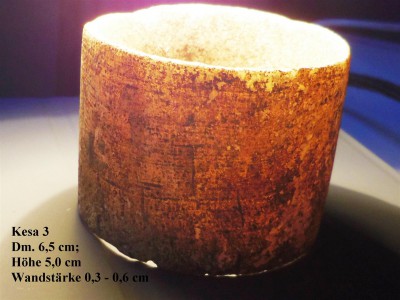

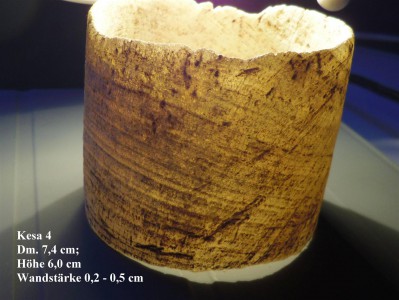

Here the authors do not handle their main source Scheffler with due care either, because they write (translated from French): „The measurement can be different, the diameter fluctuates between 5cm and 8cm. The length of the cylinders is very variable, between 6 and 15cm“ page 135). It is unknown to me where this general statement comes from. I rather think it can only refer to „large kesa“, because „working kesa“ consist of smaller cylinders. Within the five value grades detected by Scheffler (the authors speak of them too), he describes the height of the nine cylinders of the smallest grade put on top of each other to be „from the finger tips of the outstretched hand to about three inches below the inner crook of the elbow“. Assuming that other people’s arms may be longer than mine, I estimate this measurement to be 40 – 45 cm. Divided by 9 that corresponds to an average height of 4.5 to 5cm per cylinder. In fact Scheffler was given a kesa potaka kameka (= grade 1) as a present when leaving Choiseul. The nine cylinders of this kesa showed a total height of 45cm (Davidson 1996:44). „The fifth size should reach to the center of the biceps“, Scheffler writes (1965:201). I estimate this measurement to be about 55 – 60cm, that is about 6.5cm per cylinder. See also the title picture for this. Thus a single cylinder within the five value grades mentioned by Scheffler measures from 4.5 to 6.5cm on average.

The authors‘ statement that „working kesa“ are very thin, that their thickness is hardly ever more than 2 mm, cannot be allowed to stand either. The wall of all cylinders known to me is vertical on the outer edge and slightly convex at the center. All cylinders measured by me have a thickness of 2 – 3 mm at the edge, but of 4 – 6 mm in the center.

3. Items used by me for comparison

a) Three kesa cylinders which are part of a complete kesa and one single cylinder. All four are thin-walled and clearly „working kesa“. They are shown below, each of them in normal lighting and against the light. Measurements are indicated on the pictures.

b) A tube of Kuphus polythalamia as well as fractions of a tube.

4. Kesa are not made from Kuphus

4.1 Statement of the authors

Translation (p. 135): „To this day all available texts on kesa assume that these cylinders are made from fossil Tridacna shell. It is true that the first type of kesa, „large kesa“, shows the usual signs of fossilization and decay of Tridacna, but these are not found at all on the very thin ones. When compared thoroughly, it is obvious that the materials of the two kesa types are different. Only the thin kesa show a „piqueté“ on the surface, which is similar to growth lines. To solve this matter Philippe Bouchet, specialist for molluscs at the Muséum d´Histoire naturelle-in Paris, and his assistant Rudo von Cosel have dealt with this question. Von Cosel analyzed a „working kesa“, a „large kesa“ and a sample of a Kuphus tube in Paris. He holds that „large kesa“ are indeed made from fossilized Tridacna shell, whereas he thinks that the thin kesa, which clearly show growth lines under the microscope, originate from Kuphus tubes.“

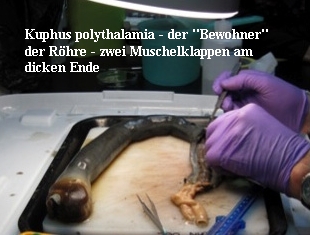

Later on they say that: „These molluscs (meaning Kuphus) are not capable of boring into wood and live in mangrove mud, mainly on the Philippines, but also on the Solomons. The „head“ is a small, two-lidded shell 1 to 2cm long, and the soft body protects itself by means of this strange and large chalky formation, which is buried in the mud. This tube can reach 2 meters in length, the tube tapers from 2cm at one end to 10 cm at the other. „So this cylindric form was cut up to obtain the basic money. The different diameters of the kesa (cylinders) piled up one on the other, are due to the gradual cutting of the tube“ (translated from French).

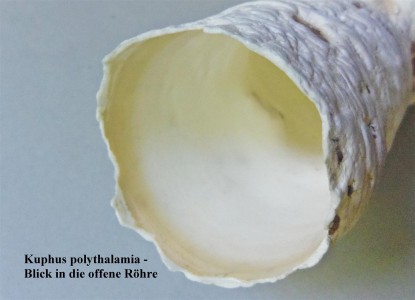

4.2 What is Kuphus?

The book describes this animal well, page 136 shows a picture with a heap of such tubes. In the pictures above you see a Kuphus tube in my possession and the picture below shows the animal that lives in the tube.

Only one Kuphus species exists, Kuphus polythalamia (Linnaeus, 1758), so there can be no mistake.

4.3 Counter-arguments to statement 4.1

a) optical

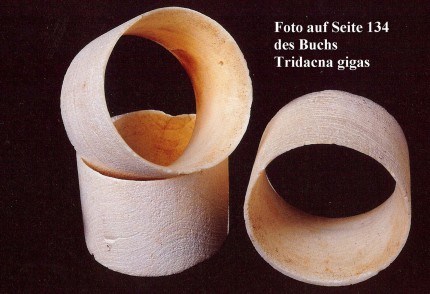

- The three cylinders pictured in the book on page 136 clearly show undulated growth lines typical of Tridacna shell. See the wonderful barava plate on page 198, which is doubtless made from Tridacna and shows the same lines.

-

- Held against a powerful light source, the average „working kesa“ examined by me show growth lines too (see above).

- The Kuphus tube does not show any structure lines when held against a powerful light source, the image is free of any growth lines (see below).

- The fractured surfaces of a Kuphus tube and a kesa cylinder are quite different in structure. The Kuphus clearly shows a fine radial structure, whereas the fractured surface of kesa is similar to the typical „shell fracture“ (see the photo below for comparison). Dr. Winfried Werner, deputy director of Bayerische Staatssammlung fuer Palaeontologie und Geologie in Munich, analyzed both fracture surfaces under the microscope and confirmed that the structures of the two materials do not match.

-

- Kuphus (im Gegenlicht ohne Wachstumslinien)

So growth lines are typical of Tridacna (as the authors write themselves) but not of Kuphus! The authors defeat themselves with their own weapons and contradict themselves. It is a mystery to me how the scientist cited in the book could come to a converse conclusion.

b) physical – methodical

- Because of the last sentence in paragraph 4.1 I really doubt that the authors ever held kesa cylinders or a Kuphus tube in their own hands. The kesa „piling up one on the other“ have no different diameter! They must have exactly the same, otherwise they could not stand one on the other (see title picture). It is not possible to make them by „gradual cutting“ of a conical tapering tube.

- The Kuphus tube tapers from 10 to 2cm, as the authors mention. Hence it is not cylindrical as the authors say, but conical. The tapering of the tube makes one doubt if it would be possible to make from it just one cylinder with a vertical wall.

- Even if that were possible, which I doubt, it would take eight more pieces with exactly the same inner diameter to make a kesa.

- All available photos of Kuphus tubes show that the tubes are usually buckled and distorted (see above).

This examination shows likewise that the statement of the authors, kesa were made from Kuphus tubes, is absolutely unrealistic.

5. Do kesa consist of Tridacna shell?

The assumption that kesa consist of Tridacna shell is backed by the following authors:

- Scheffler believed that kesa were made from fossilized Tridacna shell (1965, p. 200).

- Miller reports that an excavation on the traditional Nuatambu site in 1978 confirmed Scheffler’s assumption (1978, p. 292).

- On site, Lautz (2008, p. 96) also came to the result that kesa consist of Tridacna shell.

- Richards (2012), who is cited as a source in the description of the kesa cylinders in the BritishMuseum’s collection, replied to an inquiry from Prof. Denk: „In brief, the kesa are not made of kuphus which has a powdery deposit and a tube narrower on one end than the other. Kesa are made out of a Tridacna species that has long term fossilisation. Microscopic examination shows some kesa are made parallel to the grain and other were made at right angle to it“.

Thus if kesa consist of shell material and Kuphus can be excluded as the material of origin, Tridacna gigas is the only remaining option. It is the only one of nine Tridacna species which produces shells of the required size and especially of the thickness needed to produce such cylinders.

An interesting version comes into play by Richards (2012). He writes: „My belief is that the species of Tridacna used for kesa is unlike the species used elsewhere for rings etc. (neither are identical to the Tridacna species alive today). This is to say that the Tridacna deposit from which kesa were made was very local to Nuatambu, and was probably exhausted by the early makers of Kesa“.

This theory together with the preceding remarks would mean that fossilized Tridacna material was lifted in the course of the formation of islands and contained species not alive anymore today. This assumption is backed by the fact that it is so difficult today to identify the material of kesa exactly. This is in line with a statement by scientist Dr. Werner (2012, personal communication) that some features of a kesa cylinder examined by him optically indicate Tridacna, but not all do so. He reported to me discoveries of fossilized Tridacna off the coast of Kenya with an estimated age of 128,000 years. It is possible that material changes have occurred in the course of such a long time span. The expertise cited in paragraph 6, which came to the result that kesa and the examined piece of „clamshell“ showed great similarity, can be seen in this context. One of the circulating myths about the origin of kesa tells that it was produced by a sea god named Laena. It proved to be insufficient and Laena promised to make more. However, he lost his life in a fight with a snake, so that people waited in vain for more kesa. That was the reason for the scarcity of kesa today (Davidson 1996, p. 36). This could also reflect the exhaustion of the „stock“.

6. Curator: resistant to advice:

The authors of the book write that „this interpretation (by the Paris scientist von Cosel) confirms that of Lawrence Foanoata, curator of the museum in Honiara, who believes that kesa originate from dump worms“ (p. 136). This gentleman should really know better, because in 1991 our club member Koschatzky ordered the examination of three materials on behalf of Maria Lane, formerly curator of this museum in Honiara: a piece of a Tridacna axe blade (clamshell), kesa and a piece of the „dump worm“ referred to as „Toledo worm“ at the time. The X-ray analysis made by the Staatliches Forschungsinstitut für angewandte Mineralogie Regensburg at the Regensburg University came to the clear result that kesa and clamshell consist mainly of aragonite, whilst the other material consists almost exclusively of calcite. The microscopic examination also showed great similarity of kesa and clamshell. The other material differed from both. The conclusion of the expert: „Kesa corresponds with clamshell“. The expertise was written in English to be useful to the museum in Honiara. Unfortunately Mr. Foanoata does not seem to know anything of it.

7. Wrong Citations _ Poor Research:

Throughout the whole article about kesa, it is difficult to recognize the sources of the statements made. The somewhat careless handling of Scheffler has already been criticized. Something similar applies to the second source, Capell (1943). I will take the last paragraph on page 137 from the book as an example. It is taken almost literally from the work of Capell, but besides some serious translation mistakes from English into French it also contains a distorting alteration concerning kesa.

The last sentence in the book reads „Il recevait alors un cochon et le nombre de rouleaux de kesa correspondant à la valeur de l´homme tué“. Translated: After that he receives a pig and the number of kesa rolls corresponding to the value of the killed man.

In Chappell’s book (1943, p. 24 – 25), however, this sentence reads as follows: „He is given a pig and a number of strings of kesa equal to the number of men killed“. „Strings“ were changed to „rolls“ by the authors, because otherwise it would not have matched kesa. From the context in which Capell wrote this sentence, I deduce that he is referring to Thurnwald, who speaks not of Choiseul but of the customs on the island of Bougainville. He had spoken of „strings of shell-money“ before. Thurnwald was already cited by Capell on page 23 with the annotation that a woman receives „shell-money (kesa)“ from the clan of her husband when her husband dies. I suppose that Capell added the term kesa in brackets because of his erroneous opinion that shell money and kesa were one and the same. The whole passage most likely does not refer to kesa but rather to shell disk money. By the way, Capell never went to the Solomons but just evaluated available literature.

Finally the authors write on page 137: „Pour Scheffler et Capell, les kesa appartenaient à une famille ou à un clan, au meme titre que les cocotiers, et à l´inverse d´un cochon ou d´un jardin, qui représentaient des biens individuels“. Translated: In Scheffler’s and Capell´s opinion kesa belong to a family or a clan with the same right as coconut palms, in contrast to a pig or a garden, which can belong to an individual. This, however, is not true as far as Scheffler is concerned. He writes clearly that many kesa were in the hands of „private“ individuals (Scheffler 1965, p. 117).

8. Conclusion

a) The authors‘ statement that „working kesa“ is generally made from Kuphus tubes is wrong! It is untenable in view of optical and methodical findings which indicate something quite different. In any case, it does not apply to the cylinders examined by me (parts of a complete „working kesa“ of average size). The authors also contradict themselves.

In addition a scientific expertise from 1991 says clearly: kesa are made from clamshell, that is from Tridacna.

The place of production was quite apparently limited to the small island of Nuatambu off the east coast of Choiseul. Possibly the kesa cylinders were made from longterm fossilized Tridacna material which contains species not alive anymore.

b) Close examination shows that the authors handled the matter too carelessly as well as an obvious lack of fundamental knowledge. This is confirmed by an analysis of the literature mainly used by them. It is all the more amazing that they have planted such a statement.

–> 89-1-2013 Bibliography „Kesa…“ B.Rabus